This is why we need to redefine climate change narratives

How can we communicate about climate change and carbon technologies in a way that resonates with more people? The answer, according to a panel of experts at a recent seminar hosted by CORC and Novo Nordisk Foundation, is not just disseminating more scientific data but fashioning resonant stories that cut across diverse communities, transcending raw information to prompt meaningful action.

In a time when the stakes of climate change grow ever larger, the necessity to transform how we talk about this global challenge have reached critical importance. As scientific consensus solidifies, the need for an effective means to communicate this urgency becomes paramount.

With an ambition to inspire more people to communicate more effectively and based on science and facts, CORC and Novo Nordisk Foundation hosted an event on communicating climate technologies with four thought leaders sharing their experiences.

Their insights, drawn from fields spanning journalism, research and communication, converged on a central thesis: the power of narrative in steering conversations on climate change towards actionable outcomes. A change of narrative is needed—one that taps into emotion, aspiration, and relatability to inspire genuine engagement.

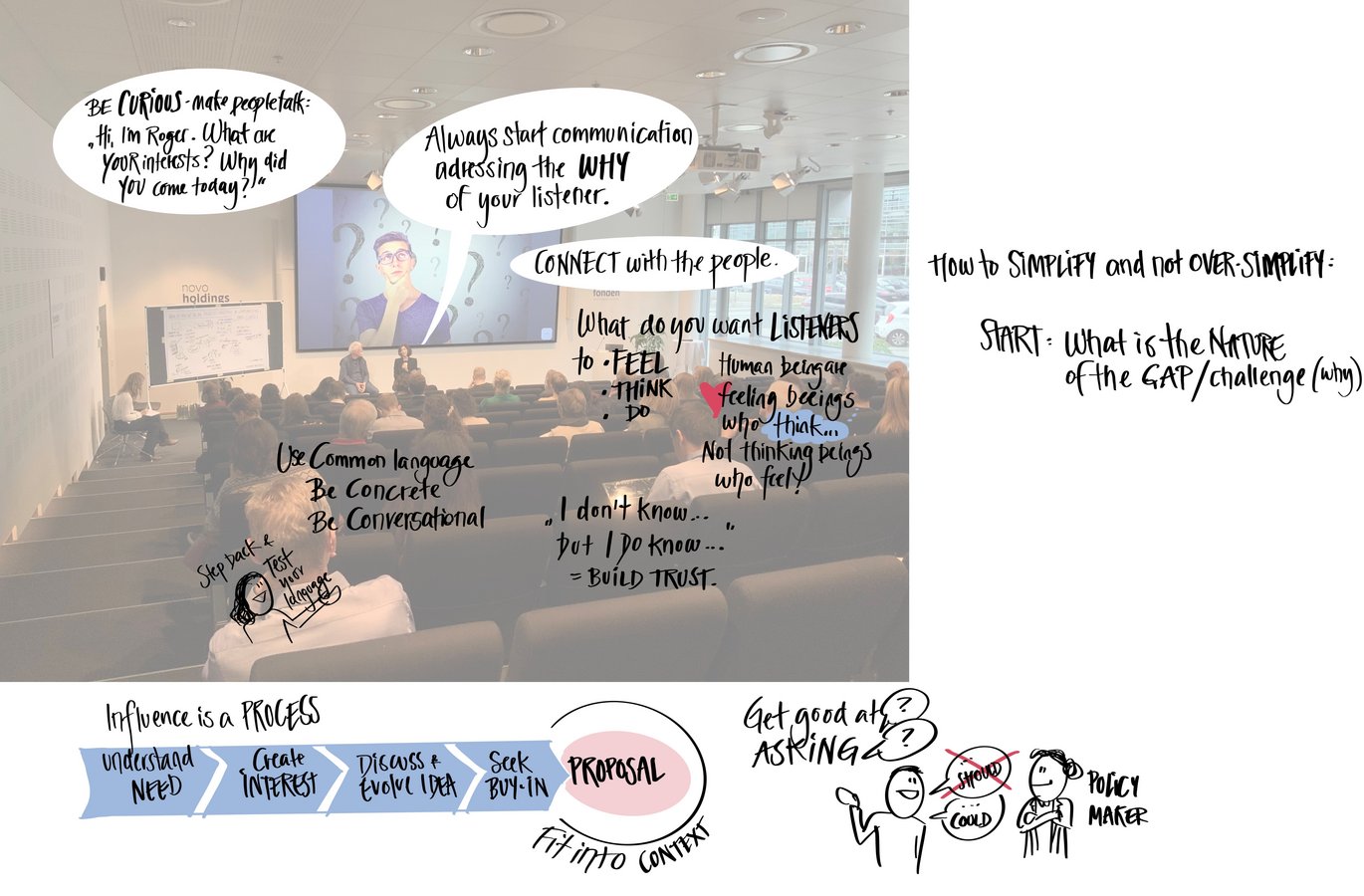

Two of the speakers, Amy Aines, author and communication expert, and Roger Aines, Chief Scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Lab and Senior Advisor for Carbon Dioxide Removal for Energy and Innovation in the US government, shared their insights on engaging policymakers and the public in meaningful conversations about the complex issue of climate change.

Amy Aines highlighted the crucial disconnect between scientists and policymakers. She emphasized the necessity of clarity in communication and understanding the starting point of the audience. "You can talk to Senators and representatives who nod along without truly comprehending. Understanding their perspective is key to making an impact," she stressed.

If scientists get half an hour to explain their research to policy makers they will often make sure to give all the information that they themselves believe to be relevant. But as Amy and Roger made clear, policy makers - and honestly most other people - do not make decisions based on a lot of information. Rather they need to understand and feel why something is important.

“When you're talking to people about something that's wrong, it captures an emotional response. So starting with ‘why’ instead of ‘what’ also gives you a chance to provide context for the people that are listening to you,” Amy Aines points out.

Roger Aines echoed this sentiment and stressed the need to infuse hope into the climate narrative.

“We have an obligation as climate scientists not to forget hope when we talk about all the challenges that are in front of us. It's very easy to say all the things that are hard, all the things that are difficult, all the other technologies that we don't like, because it's not our technology. We have to not do that. We have to be very careful to say we can fix these things.”

Acknowledging imperfection was also a recurring theme in their discourse. "Admit what you don't know but swiftly shift to what you do know and are confident about. This builds credibility and trust," Amy Aines advised, urging transparency in discussions.

Most importantly the science needs to be easily understood - and this does not mean ‘’dumbing anything down’, Roger Aines underscored:

“You've insulted the listener to the point that you're going to fail. You're already assuming that they are not capable of listening to what you have to say, and you might as well not do it. We prefer the phrase ‘extracting the essence’. The fact that there are a thousand details that are important to your work, is not part of a new conversation with a policymaker or a friend you met at a bar where you're telling them about your work. You need to start with the important stuff.”

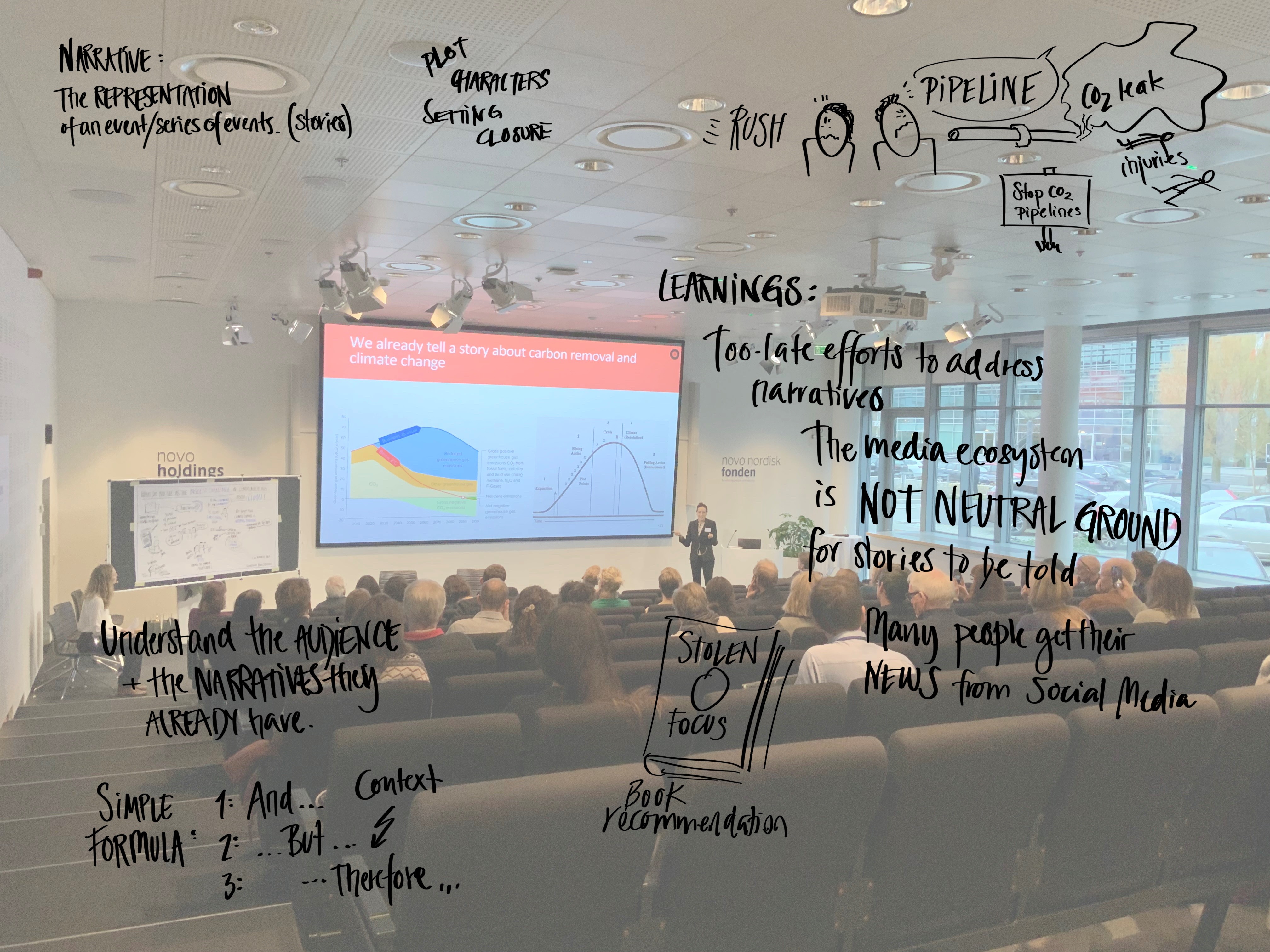

The power of narratives

Holly Buck, Assistant Professor of Environment and Sustainability at University at Buffalo, does a lot of community engagement, knocking on doors in neighbourhoods, and asking questions as part of her research. And her experience is that you need to reshape the nature of information into stories that resonate with the people in front of you. But this does not mean neglecting the facts, it all has to be part of the conversation, she said:

“The facts are really important, and people are really hungry for understanding things. I've gotten lots of questions about this when I do community engagement, because people are really smart. They want to know this thing you are introducing them to is a genuine thing. They want to see some numbers about what the emissions of the materials going into this thing are.”

She strongly believes that narratives and stories are the most efficient way of communication the often-hard facts of climate technologies. She explained that narratives embody a structural underpinning of how humans make sense of the world across cultures and time.

In the context of carbon removal and broader science communication, the traditional transmission model of communication, where information is sent and received, has been redefined, she explained. Communicating about carbon removal isn't merely transmitting data; it's narrating who we are as a society and the choices we make.

Holly Buck underlined the importance of contextualizing narratives within the broader societal fabric. She advocates understanding existing audience narratives about climate change, land use and industrial roles before making the story - as these are the narratives familiar to the audience.

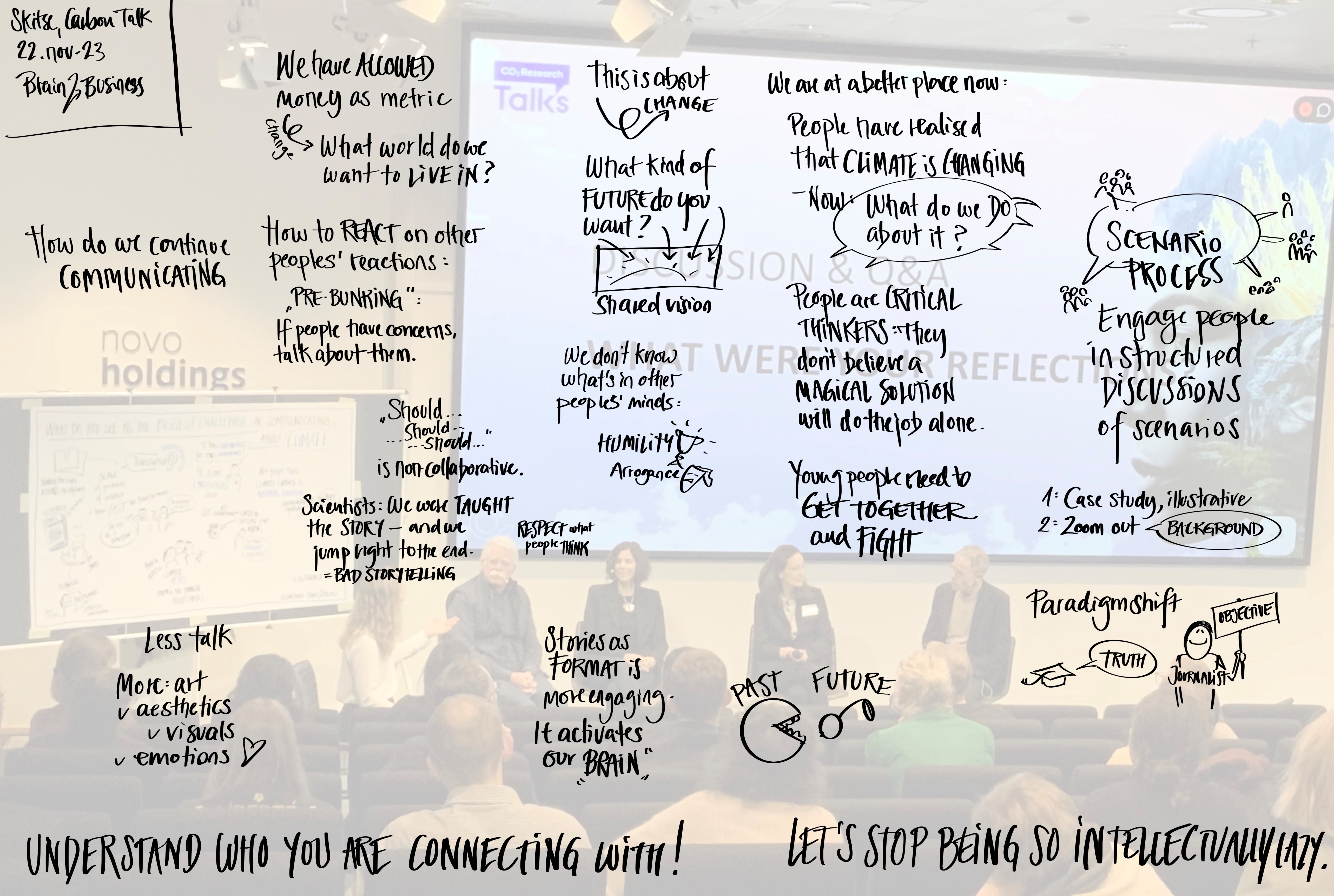

Positive future visions as an obligation

Climate change narratives often seem quite dystopian - and very few people feel motivated by this way of communicating. The last speaker of the day, Peter Hesseldahl, a Danish tech journalist and author, delved into the realm of envisioning a future propelled by optimistic and aspirational narratives. He argued for the power of positive visions in steering societal actions towards sustainability and innovation.

With examples such as the advertisements of the company Tesla, showing an attractive life with solar panels on the roof and a nice-looking car in the driveway, he pointed to the importance of a positive future narrative. He advocated for a momentary suspension of negativity to explore positive outcomes and engage in a dialogue focused on aspirational visions.

He envisions a paradigm shift in economic models, one centered around biological, living systems rather than conventional industrial or digital technologies. Drawing a sharp contrast between viewing society as a machine versus as an ecosystem, Peter Hesseldahl underscored the need to shift from linear consumption models to ones focused on resilience, circularity and regeneration. He advocated for a transformational shift towards an economy driven by balance rather than infinite growth, rooted in the values of natural systems.

“We used to think of society as a machine or as a big computer. And I think we have to think about society as a living organism or an ecosystem. And it really changes the words that you use. If it were a machine, you would have linear consumption. You would have short-term focus. All these concepts that we have from capitalism, it's a different way of thinking about what is the value creation that's happening in society.”

In conclusion the event showed the complexities of communicating climate change, but also the urgency of a narrative shift that goes beyond mere awareness to elicit empathy and proactivity.

Four ways to improve climate change communication |

|---|

|